Google may be feared and secretly envied throughout tech circles for its industry-disruption track record, but in at least one respect, companies are grateful for Google’s propensity to plow the road.

The Google Glass experiment has provided some very public lessons about what consumers are willing to accept in wearable tech and what they positively will not stand for — at least at this point in time.

Manners and Other Expensive Lessons

Thanks to Google Glass and some brave early adopters, society by and large knows that to wear Google Glass in a bar or social setting is to put oneself at risk. Glass also tends to attract the attention of law enforcement, especially when the wearer is operating a moving vehicle.

In short, this technology is new and very different, and Google perhaps would have been better off if it had introduced it in a more circumspect and gradual manner. In scenarios where Google Glass has a clear, nonthreatening use — such as providing support to a repair technician — it is seen as a valued tool. So thank you, Google, for providing that very expensive lesson for free.

Make no mistake: Wearable technology is clearly poised to become very important, much like cellphones were more than a generation ago. However, like the introduction of cellphones into society some 20 years ago, companies and consumers are going to have to learn how to behave when using the new technology.

We are now getting the chance to watch another company’s attempt to unlock the mysteries of wearable tech.

Salesforce.com has introduced Salesforce Wear, an initiative in which it provides developers tools to build apps for wearables across a wide range of devices offered by ARM, Fitbit, Pebble, Philips, Samsung and others.

All the developer has to do, as Salesforce.com describes it, is build a use case.

It is a marvelous plan, especially from the perspective of Salesforce.com, which hopes to see its branded apps on a slew of devices used in a wide range of industries.

The wearable technology space is shaping up to be a 50-million unit market this year and will grow to more than 180 million in 2018, according to IHS. So, this can only be a good thing — unless a platform or device type is attacked on a scale equal to, say, last year’s Target breach.

“Threat levels will continue to rise as cybercriminals find new ways to access data and exploit weak links in the ecosystem,” said Nicholas Evans, VP and general manager within the office of the CTO at Unisys.

Wearable technology could well become an enticing vector, he told CRM Buyer.

“While Salesforce Wear will certainly aid businesses looking to implement wearables into their mobile strategy, several barriers and important considerations still exist for entering the Internet of Things market,” Evans warned.

No Second Chances

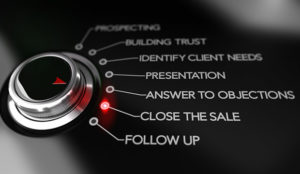

Companies that hope to use wearable technology in a customer-facing manner must navigate these barriers and challenges very, very carefully, as end users will not be inclined to give second chances if a mistake is made.

“For wearables, in particular, it is important to address the new types of data that can now be captured, transmitted and stored, as well as how this data is used,” Evans said.

Especially for customer-related apps and industrial and commercial uses, personal data will be collected and stored — think health records, driving behavior and general whereabouts.

“Companies entering the wearable space will still need to develop new ways to secure and support these new classes of devices and their associated data,” Evans pointed out.

Good luck with that. So far, even the most obvious targets of cybercriminals — retailers — have not learned to secure their customer data.

One possible answer is to establish an initial presence in wearable tech only with the most benign applications. Experiment when your customers’ most sensitive data is not at stake, and then move on to the serious stuff.

Of course, the question is, which use cases are benign but still offer revenue opportunities?

Here’s one example: Ringly, a startup created by eBay and Etsy alums and backed by First Round Capital, Andreessen Horowitz and PCH.

Ringly makes connected jewelry that alerts the person wearing it to phone calls and text messages. It targets women who might not hear their phones when they’re tucked in purses or desk drawers.

The Ringly mobile app, which supports iOS and Android, pairs with the ring via Bluetooth LE and pings the wearer when she receives a text, call, calendar alert or email. It will even notify her if she leaves her phone behind.

Granted, this is not as sophisticated as a Fitbit-like bracelet that contains a valued customer’s user profile — a user case suggested by Salesforce.com. However, it could be a training wheels version of that use case, which is what many companies may need to experience before wearable tech can go mainstream.