![]()

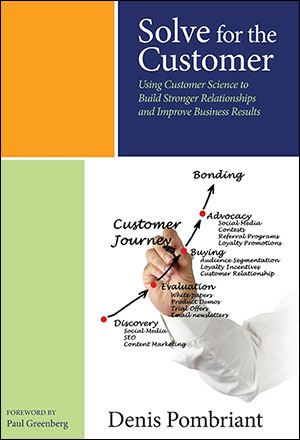

Solve for the Customer: Using Customer Science to Build Stronger Relationships and Improve Business ResultsBy Denis PombriantCreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform March 5, 2015, 190 pp.$14.99 Paperback We all know customers have changed. They can voice their dissatisfaction with you, complete most of the buyer’s journey without you, and even seek out support and service without you.

If you’re a business, you have two questions to ask yourself: 1) Do you really want to become unnecessary to your customers? and 2) What are you going to do about it?

Denis Pombriant is assuming your answer to the first question is a resounding “No!” and in Solve for the Customer, he provides solid, realistic advice to help you answer the second question.

Pombriant, a regular contributor to CRM Buyer, has been up to his elbows in what used to be known as social CRM, or sCRM, since its inception. sCRM has become so well accepted it’s generally thought of as an integral part of CRM today. Never one to become bedazzled by technology, Pombriant has kept one eye trained on customer behavioral shifts as vendors have attempted to chase them shifts with new technology.

If you’re hoping for a how-to book on what shiny new technology to buy, Solve for the Customer is going to disappoint you. It is a far more interesting book than that — it examines the behaviors and the process changes that need to be made in response to those changes by companies that hope to remain relevant to the evolving customer.

Get the Processes Right

The book starts by outlining the conflicts arising from the empowerment of customers — largely by social media — and the slow movement of companies to respond in kind. One of Pombriant’s long-time favorite concepts is the “sucks score,” which he uses to provide immediate evidence of the customer’s power to control the conversation. To find your “sucks score,” google your company’s name and the word “sucks.” The number of hits that come back provides a grisly and accurate measurement of how many customers out there are talking about you in a negative way.

Pombriant outlines other problems — with current metrics for customer satisfaction, with churn in the expanding subscription economy, and with business models that are not only failing to keep up, but also holding businesses back.

After laying the groundwork, Pombriant leaps into solutions that key in on two ideas that are not Pombriant’s own, but which are applied to the issue of the changing customer to varying degrees, more so at successful businesses.

First is the customer moment of truth, those instances when the business and the buyer intersect. They can go well, or they can go badly. That leads directly to the second — Pombriant’s use of the Anna Karenina Principle, an idea popularized by Jared Diamond in his very different book Guns, Germs and Steel.

That concept reflects the first sentence of Tolstoy’s book: “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Swap out “family” for “customer” and you have the idea. Every customer has specific reasons for dissatisfaction; the trick becomes to develop a flexible process for addressing those areas of dissatisfaction in a timely way, and with employees sufficiently empowered to make real changes.

Doing that requires an attitudinal shift. We’ve treated the issue of addressing customer issues in the same way we’ve treated every other business problem in the last 25 years. We’ve thrown standardized processes at customer issues, then worked to wring out every bit of productivity from those processes.

That would work if customer issues were confined to a few consistent problems. However, as customers have evolved, and as product mixes have become more complex, the problems that can undermine customer relationships have become more varied. They’re now not about product — they’re about processes. Products are easy to fix, but processes are a different matter altogether.

Tap Into Customer Communities

How do you cope? Pombriant suggests charting all of your moments of truth to understand where things may go amiss, and planning ways of dealing with them ahead of time. He defines the “customer lifecycle” as a cascade of moments of truth — meaning that businesses have a chance at each point in the relationship to get that cascade to fall the right way.

Doing so requires empathy on the business’ part and the ability to bond with the customer, but it also requires a change to the processes used to keep moments of truth working toward customer satisfaction.

To discover what those changes should be, Pombriant recommends using communities — places where your customers can tell you what they need and want directly. He backs up his recommendation by spending the rest of the book explaining their value through examples like Symantec, HP and MetLife.

Those companies have been successful in changing attitudes internally, using the right technology, and — perhaps most importantly — using the right kinds of communities to achieve the right goals. Pombriant outlines all of these approaches and walks the reader through the development and refinement of each community, a nod to the idea that keeping up with the customer is a race without end.

The one thing all of Pombriant’s example companies have in common is the willingness to let go of old processes and implement new ones, even when it may result in hearing customers say things that are painful or threatening to the status quo.

Hearing those things is exactly what successful companies want — because they know that hearing about them in proximity to the moment of truth allows them to make changes that can remedy the problem. In fact, smart use of communities can allow companies to anticipate those moments before they happen.

Solve for the Customer is an exceptionally helpful resource for companies with the courage not only to embrace the idea of change, but also to work with their customers to define what those changes should look like.

The trends it identifies are impossible to dispute, and the suggestions it makes are backed up by real-world results. This is an important book — ignore it at your peril.